Finding Our Voices Through Witnessing the World

I am not, by any means, a master storyteller. But I learned that no storyteller can achieve mastery without being a sharp observer. Where Naley and I lacked technical skill, we more than made up for it in tact and awareness. Where we excelled was in shifting the role of passive observer to one of true containment—learning how to listen to another’s reality as it exists for them. I am talking about truly seeing someone for who they are, as opposed to filtering their account through personal lenses.

Perception is shaped; we are, after all, social creatures. We have an instinct toward belonging, and that makes us highly adaptable. But this instinct isn't about blending in; it's about the effect that awareness produces when it’s directed toward another.

Every story contains that potential when it meets a conscious observer. Something within us materializes into reality when we are seen by another. Reflecting on how Naley and I chose to approach this process for our documentary, we began to see this principle in motion.

Being a good listener is a formidable asset in any storyteller’s repertoire. The technique is accessible to anyone who wishes to attune to its ways. The simplicity of listening often poses as a passive act, when it is anything but. Listening functions like a scalpel in the hands of a surgeon. It can amplify or diffuse energy, and it can activate the observer with enough presence to walk toward fate.

There is a good reason genuine curiosity is crucial to the fulfillment of just about anything. Curiosity sparks, but it can also just peek its head out and lure you in. I call it the ability to “walk with another”—as you take me down memory lane, grant me entry into your imagination, or perhaps lead me off a cliff at the sudden arrival of your greatest idea. Intentional inquiry has the potential to guide a person into piecing together parts of themselves into meaning. The listener’s questions seem to tap into personal curiosity, yet the experience somehow feels shared between observer and observed. People want to be seen because this dynamic fuels the process of becoming. Or what I like to call, a life well-lived.

So when we saw how most of the world’s marginalized communities share a common thread of invisibility, we recognized the lack of curiosity as emblematic of something far more universal. Naley and I were drawn to those corners of the planet where entire communities were pushed to the periphery, as if society were trying to sweep dust under a rug. The world is ripe with stories that have been brushed under that rug.

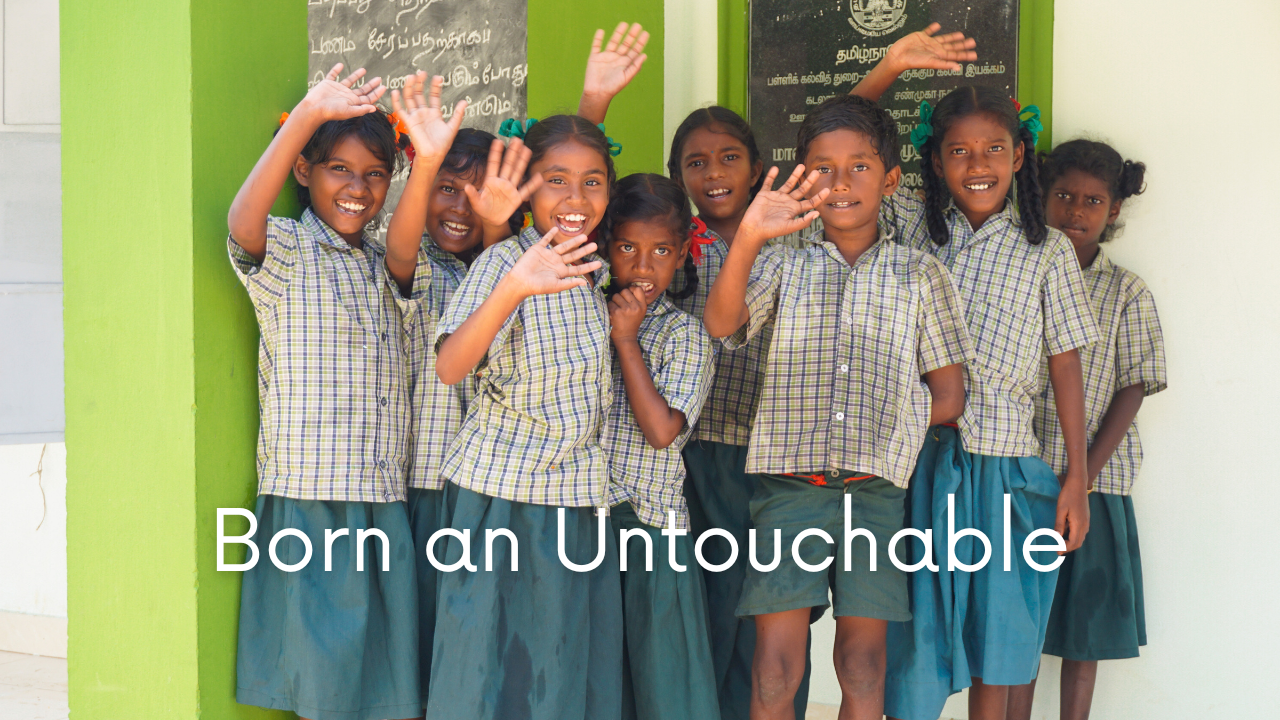

In Tamil Nadu, we worked with several Dalit and tribal communities supported by the charity Bless Foundation. The people we spent time with welcomed the opportunity to share part of their lives with us. We witnessed widespread institutional neglect and infrastructure that literally kept communities in the margins. Something Anthony Sami, the founder of Bless Foundation, shared in an interview stood out:

As Anthony describes, this kind of discrimination, passed down through generations, no longer needs the government to enforce the caste system. This is what is most psychically damaging to the fabric of society. It distorts how society sees you with what you think you are worth, trapping you in and weakening your will to transcend that image. Imagine what this does to entire communities, to entire bloodlines.

This internalized social outcasting runs freely on unconscious patterns without pushback. If meaningful inquiry were ever directed at why these practices persist, the system would crumble. The fact that it has not yet crumbled alludes to very inconvenient truths about our choices.

If I told you the truth of who I am, if I showed you my heart and the pain I endure, would you be able to hold me in my totality? That is a question that can’t be asked without a consequential meeting with reality. These communities reveal the fundamental failure of the human race as we applaud advancement after advancement. All these people are not simply getting left behind. They are getting buried under the pile of theoretical progress.

Naley and I believe the stories we captured on our journey were, in fact, bestowed upon us. The act of sharing a part of yourself is deeply intimate. Humans wish to be perceived when they feel safe enough to do so. It was our responsibility to build trust by demonstrating our capacity and being clear about our intentions.

Human instinct often sees vulnerability as an existential threat. But when that vulnerability has been engineered by ancient systems, it becomes our highest priority to affirm their experiences within the context of their circumstances—to acknowledge their pain and their presence.

The interviews we conducted prove how much people value the same things in life. The persistent denial of these things to some populations over others does not need abstract determinations; it needs our awareness to actually transform. Part of me feels our intellectual understanding of all the human suffering and injustice on this planet is getting in the way of true confrontation with its reality. Because with all this knowledge, with all this accessible information, we should not feel as powerless as we do in the face of human and environmental crises.

When I think about the people Naley and I have met on our journey so far, I think about the parts of them that stay with me long after we move on. We have had the privilege of witnessing what is innately special about the human spirit. It makes me more committed to presence, despite the reflex to turn away.

Do you know why I love stories? Because they externalize feelings within us that never quite resolve. Stories reach those feelings deep inside and draw them out through structure—and, most formidably, through the act of being observed.